Creativity to save glaciers

Creativity to save glaciers

That of Swiss glaciologist Felix Keller, as told by photographer and Slovenian Ciril Jazbec in “Saving Glaciers,” a documentary presented during the Banff Film Festival 2023.

Half of the glaciers in the world today are set to disappear. This has been said for a long time, but now that the world seems to have suddenly become aware of the real threat of climate change, studies are being published every few months that brief us on the poor state of our planet’s health. One of the latest reports, from the States, leaves no hope for glaciers: half of those in the world today are set to disappear. Scientists at Carnagie Mellon, the university that funded the study later published in the scientific journal Science, say this.

This will surely happen, according to them, even if we succeed-which is highly unlikely-to keep global average temperature growth below 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. Studies aside, those who love mountains and frequent glaciers have noticed it with their own eyes: they are retreating at a rapid rate. This is an issue particularly felt by the outdoor community, and there are plenty of photographers, explorers, and athletes who over the years have lent and are lending their voices and their work to raise awareness and to push people to behave more respectfully toward the environment, but there is someone who has decided to do more: Dr. Felix Keller, a glaciologist from Switzerland, has set to work with his team to find a practical solution to the inevitable melting of glaciers in the Alps, and although it is not believed to be the solution system, it certainly deserves to be told.

Keller then decided to develop a complex system of snow cables that could recycle glacial melt water back into the snow to bring it back up to altitude and thus form a kind of cover for the glacier. His story was told by Ciril Jazbec in “Saving Glaciers” the documentary produced by Tent Fi and presented at the 2023 edition of the Banff Film Festival. Jazbec, who is a Slovenian photographer famous for the shots he takes for National Geographic and who had won the World Press Photo Award in the nature category in 2021 with a story that was once again about raising awareness about melting glaciers, closely followed Keller’s work and his mission to save the entire Morteratsch glacier in eastern Switzerland. What prompted Keller’s action is the alarming acceleration undergone by the glacier thawing process.

“Every time I am about to go to the glacier I am tremendously worried, because I know I will find it changed, in a new phase. In fact, every year the Morteratsch glacier loses 30 or 40 meters of its length, or the equivalent of 15 million tons of ice per year.” What is described in “Saving Glaciers” is not the first concrete action taken by Keller and his team, who had already tried covering the ice with geotextile sheets to protect the surface from the sun’s rays, which, however, may be useful on a small glacier, not on a huge ice sea like Morteratsch.

“Morteratsch is moving too fast and destroying the entire canopy; we need a natural system that can counteract the speed at which the ice is melting,” Keller explains. The documentary also includes testimony from Dr. Christine Levy, of Academia Engiadina, who monitors the health of Morteratsch and other Swiss glaciers from the air. As a scientist, her focus of study today is concentrated on identifying where the next alpine lake will form, or where the next ice avalanche will break out. It is hard to think of this as a phenomenon that can be stopped, but Keller is not buying it.

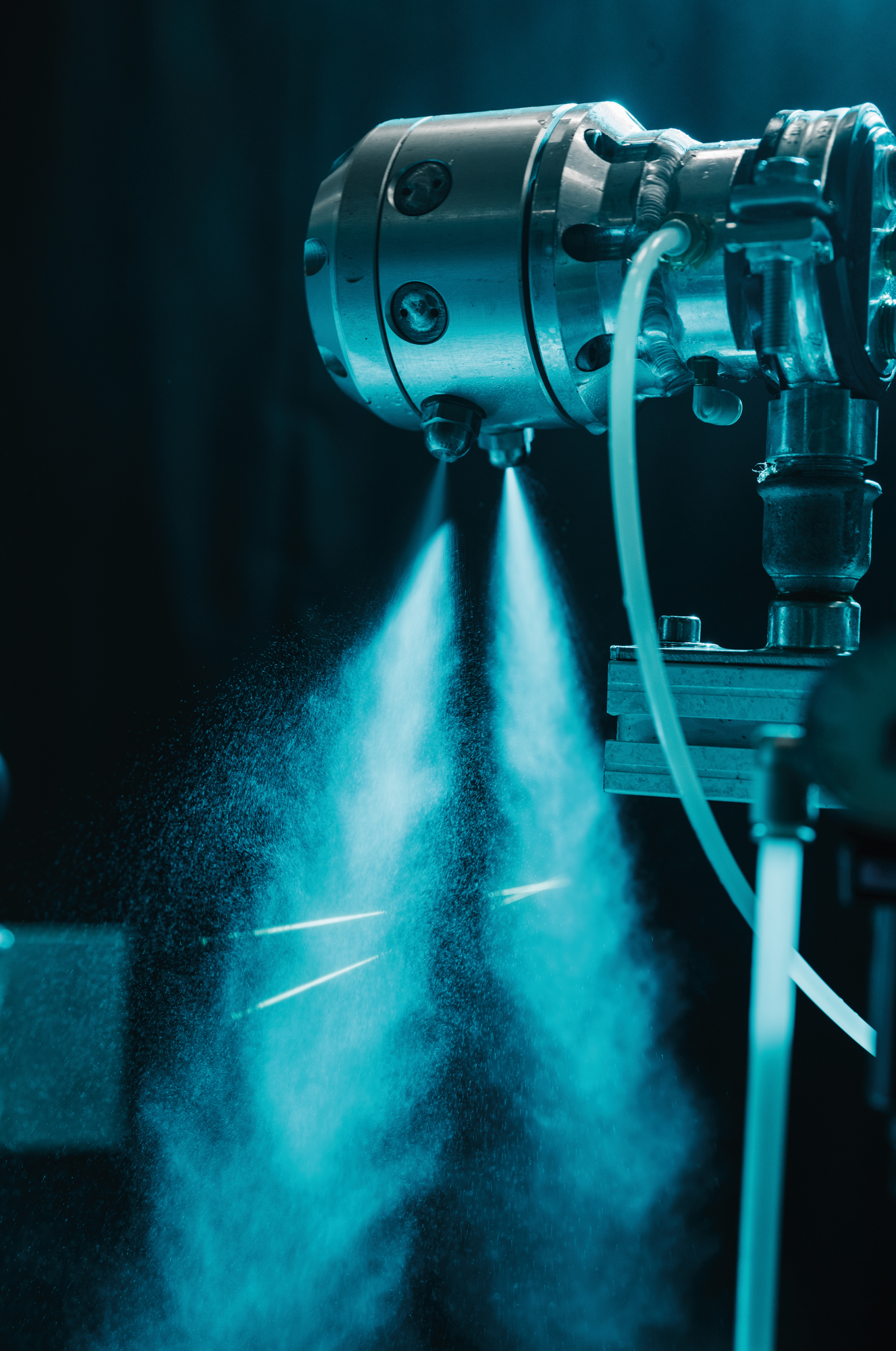

“What can I do for my children so that they too can enjoy the glacier?” This is the question beating in the glaciologist’s chest that prompted him to find a practical solution, which came in the form of enlightenment during a fishing session: “I was fishing on a river whose water comes from glacier melt, that’s where I got the idea of recycling the melt product to create new snow.” The idea, according to Keller, is simple: to preserve meltwater in the summer in regions at high altitude so that it can then be used to produce snow with which to cover the glacier with the goal of protecting it from the sun. Covering a specific portion of the glacier with snow can have important and very extensive results over the entire massif. To realize it, he asked for and obtained the help of Professor Ernesto Casartelli of the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences, thanks to whom it was possible to create both the coring system for extracting snow and the system for artificial snowmaking on the glacier. So many pieces are indeed involved in such a project, from the energy used to move the fans, to the compressed air to shoot the snow.

“Our model calculations showed that if we cover an area equal to one square kilometer with snow for an entire summer, the Morteratsch will resume growth within ten years. To do this, however, would require about 30,000 tons of snow per day. Then there is another fact: the glacier moves, hence the need to snow from above with a rope system, which is very effective because it does not depend on ground conditions and is capable of producing up to 5 tons of snow per day. When we can produce 10 to 12 meters of snow we will be able to cover the glacier for the whole year and protect it from melting for a whole summer, that would be a truly remarkable achievement. I have a special feeling when I am on this glacier: I want to be part of the solution, not part of the problem. I want to have a conscience at peace knowing that I will leave this world having done something, and not just having talked about the problem and that’s it.”