ITW & Photos: Larry Gassan

By: Elisa Bessega

Anything beyond Instagram: Larry Gassan

Larry Gassan, is a California-based photographer and former ultrarunner. He became a cult in running community thanks to his “Finish Line Portrait” project at Western State 100, and “Dead Man’s Bench” project at Angeles Crest 100 mile. I had the pleasure to have a chat with him, and it was the most hilarious interview I ever did.

Larry. I didn’t know what aspect of my work you were interested in and well, when you said you were from Italy, I thought obviously you might want to talk about Michele Graglia. I met him in 2014 when I photographed him at Angeles Crest. I saw him coming over Baden Powell Trail and my first reaction was: he’s too goddamn pretty to finish [Graglia arrived second at that race, ed.].

Elisa. [laughs]

L. No, I mean, you know: compared to him, the rest of us are just like burrows and jackasses.

E. That’s interesting [laughs], but actually I wanted to talk about your photographic work. The idea of this interview comes from a conversation I had with a friend who is a surfer and also a sport photographer. He said there is nothing interesting in shooting surf because there is only one image to shoot: the standard surfing picture with the rider right in the middle of the tunnel of a big wave. To him, surf photography would be nothing but trying to get as close as possible to that single image.

It made me think that every sport has its standard poses, some sports might have a wider variety depending on the environment and the number of different movements implied by that discipline, but at the end of the day what you see mostly in sport photography is images trying to get as close as possible to that popular standard, which makes it a little bit boring in some ways. What I like about “The Finish Line” and “Dead Man’s Bench” project, and about your work in general, is that it’s not based on any of those clichés. Why?

L. I agree. In surf photography everyone is trying to do what LeRoy Grannis did 50, 60 years ago. It’s basically all pretty much the same in running photography. What happened to me with the “Finish Line” project was that I was standing out somewhere at Western State in 2009, the sun was beating down and it was hot as hell. I finished nine 100 miler between 1991 and 1998, three of them at the Angeles Crest 100 Mile. Now I was standing there in the heat to take pictures and I was like: fuck, those guys can have it but I’m done dying out here, screw it. And so, I went back to the finish line where I set up a mobile studio.

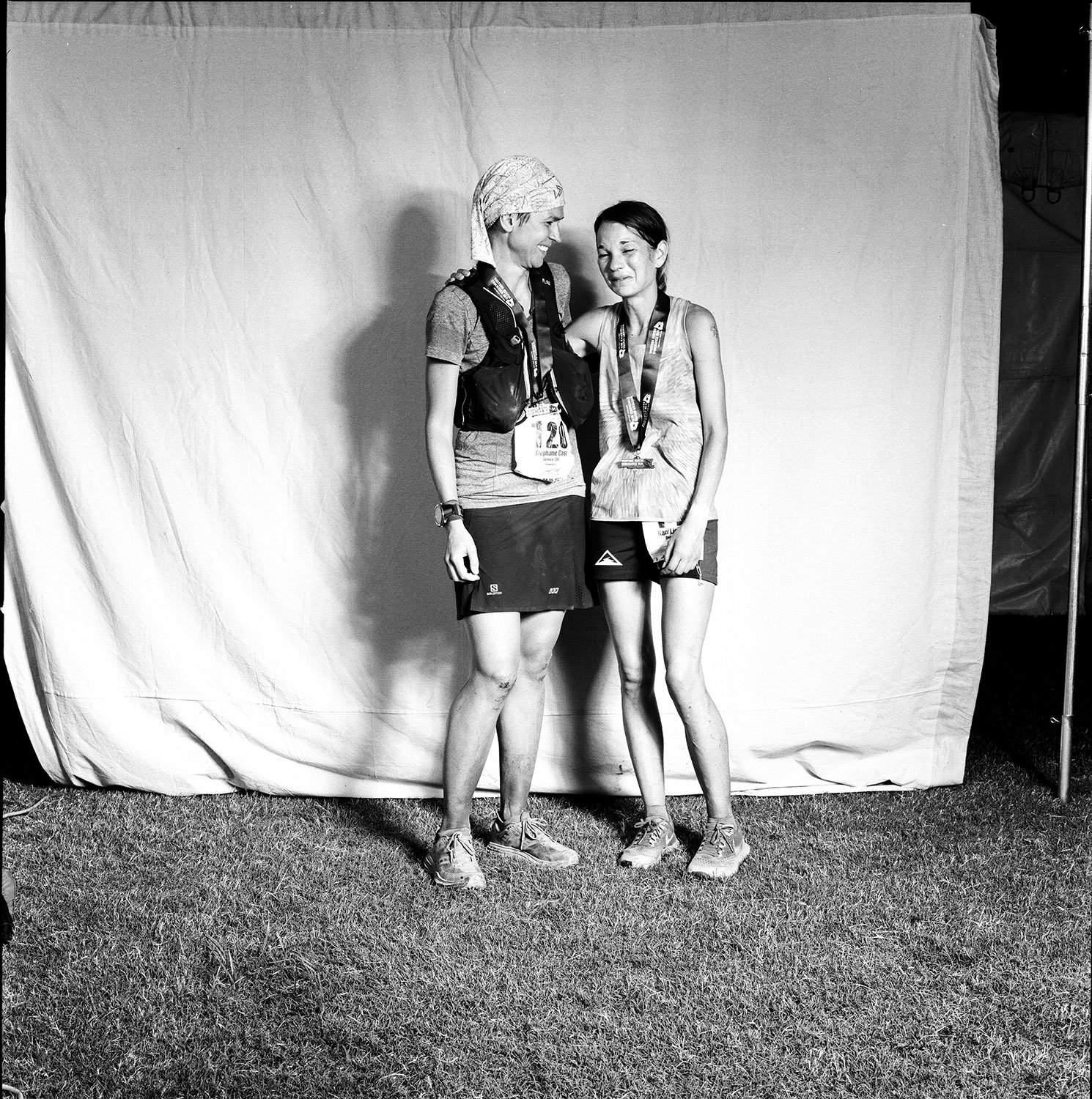

Typical running photos back then were sports photojournalism, color pictorials, and casual snapshots. Here was a unique opportunity to make portraits where none had before, so I shot each finisher with a vintage medium-format Hasselblad 500C on black and white film. As for the “Dead Man’s Bench” project, it came about because the race director at Western State fired me, as the race book editor said that anybody could take pictures like mine: “just shoot somebody standing in front of your garage, throw some dirt on him and that’s it”. He was a real shithead [laughs]. To tell you the truth, I was getting tired of that kind of finish line portrait, because at the finish line everything’s a done deal. So, I said fine, now I can do what I want. Then I saw a photo by this hilarious Taiwanese runner named Jack Chang. He had taken a picture of two of his friends at dead man’s bench during Angeles Crest, they looked like they’d been beaten up. That one, right there, was the picture I wanted to take.

And so then in the summer of 2015, I went out to Dead Man’s Bench with a minimal kit and started shooting. That bench was named after a guy that was in my running club, he had died on a trail a few miles away. It’s five miles up from the 75-mile mark, it’s four miles away from 81 miles, at a point of the race where nothing is set yet. There’s a slump in that chair: you could still just die out there or not finish, this uncertainty was interesting to me. You won’t see any of the regular shooters around because it’s in the middle of the night, it’s a pain in the ass.

And let me tell you, those nights are pretty fucking dark. I’m there, looking through the view finder and I can’t focus, I’m just guessing. Mosquitos are eating me alive and there’s all sorts of technical problems, I’m shooting with films and I know it might be garbage at the end, but when it works, the pictures are just a lot more interesting.

E. And this goes back to my question: we agreed that there are very popular and well marketable standard scenes in running photography, like those epic pictures where the runner stands on a narrow ridge, or he jumps into air with a nice view on the background. You ignored all of those conventional compositions and created your own standard scenes, where you see almost nothing about the environment, which is either a blanket or a bench in the darkness. The whole focus is on people, maybe that’s what makes them so interesting?

L. It’s because of film. I mostly use a medium format, and when you’re working with this bad boy [points at his vintage camera] you’ve gotta do a lot more fucking thinking. It forces me to shoot in unconventional spaces, and people react differently to it. With the technology today it’s almost impossible to miss getting a photo. Look at Joe McNally, for Christ’s sake. When he was in Tokyo shooting, he sent home something like 30.000 images and he said a lot of them were bad.

I mean, that’s totally legit, but I’ve said, okay, fine. Let’s step back. And let’s sort of carve out a different place. Shooting films is a pain in the ass, also after the shot itself: you’ve gotta have it processed and then spoiler alert, you’ve gotta scan it and digitize it properly in order for it to be anything beyond Instagram. And so, I’ve spent the last 15 years chasing that dragon and I’ve actually gotten somewhere.

E. So, is it just a matter of tools? Your images tell intense stories, I would say that, beyond tools, there is a precise intent, and it has more to do with documentary and photojournalism than it has with, let’s say, well-sellable aesthetics of advertising and product photography.

L. I’m making these images as a mutant hybrid of an artist and a documentarian photojournalist. And as a runner too: my 100-mile finisher experiences are essential, along with knowledge of the sport’s conventions and customs. Things happen in front of the camera, and I choose what is worth shooting. Like what happened with the picture of Maria Lordes and Alejandra. Alejandra is massaging Maria’s legs on the bench, and they’re paying no attention to me even though I’m arm’s length away from them because I’m using a wide-angle lens and I need to capture as much light as possible.

This was the keynote image of the exhibition I did about the “Dead Man’s Bench” project. Why? Because, back to your point about standards and cliché, ultras and outdoor sports are mainly white guys. And if it’s girls, it’s mainly blonde girls. There I had these two latina women working together, and nobody knew who they are. They’re not celebrities. They don’t have Insta followings. They’re not busy selling shit.

They’re just there, working together to get through the night. And I said to myself, those are the people I want. I tracked them down through friends and I told them they were in the show. They walked in, they looked up and they went like: holy shit, that’s us. That’s the whole idea. I wanted them to be excited as fuck to see themselves up on a picture that was like a meter by a meter and a half big. Advertising photography doesn’t play much part in this process. Although advertising photography might use images like that, provided they have a relevance and believability to the product.

E. How can you balance this unconventional attitude with the need to sell your work?

L. My east coast photo sensei says you can make pretty pictures that get likes on Instagram, or you can make interesting pictures. The first ones sell easier, but have a very shorter shelf life, you just have to decide what space you want to be in. It’s a trade-off, like in life. I did not have a spectacular career. I did not win a bunch of awards and that kind of staff, I was too busy chasing ultrarunning and being in the mountains and shit like that. But the reason you and I are having this conversation is because you, and someone like you, said: “this guy’s work doesn’t look like all the rest”. So of course, it’s worth it.