Text: Valeria Margherita Mosca

Illustrations: Nicola Magrin

My mountain, the Valmalenco

My mother’s family comes from Alta Valtellina and I feel a deep sense of belonging to this land flowing in my veins, but also and above all I belong to the mountains. Breathing the air, sniffing the intense presence of natural elements, contemplating the details and lines of these glorious rock giants covered in colors, makes me feel at home and alive, alive in the transcendent sense of feeling interconnected to the natural cycles that, more that in other places, here are so perfectly marked and recognizable.

Although in the history of their existence, over the course of the geological eras, the mountains have transformed and have undergone profound changes due to geological and climatic events (the glacial periods, in particular, have had a notable influence on the fauna and flora of the mountain systems, causing for example in the latter a strong dynamism, so much so that some species have been pushed, by adverse climatic conditions, towards lower altitudes), in them, observing, I can recognize the familiar image of nature in the making but that it repeats itself, and I feel reassured, because I know it and belong to it. I can recognize the altitudinal bands which tend to follow a fixed pattern and, at higher altitudes, where trees fail to grow, the habitats characterized by low and resistant herbaceous plants and, at times, the rocks and moraines, which testify the ancient expansion of glaciers.

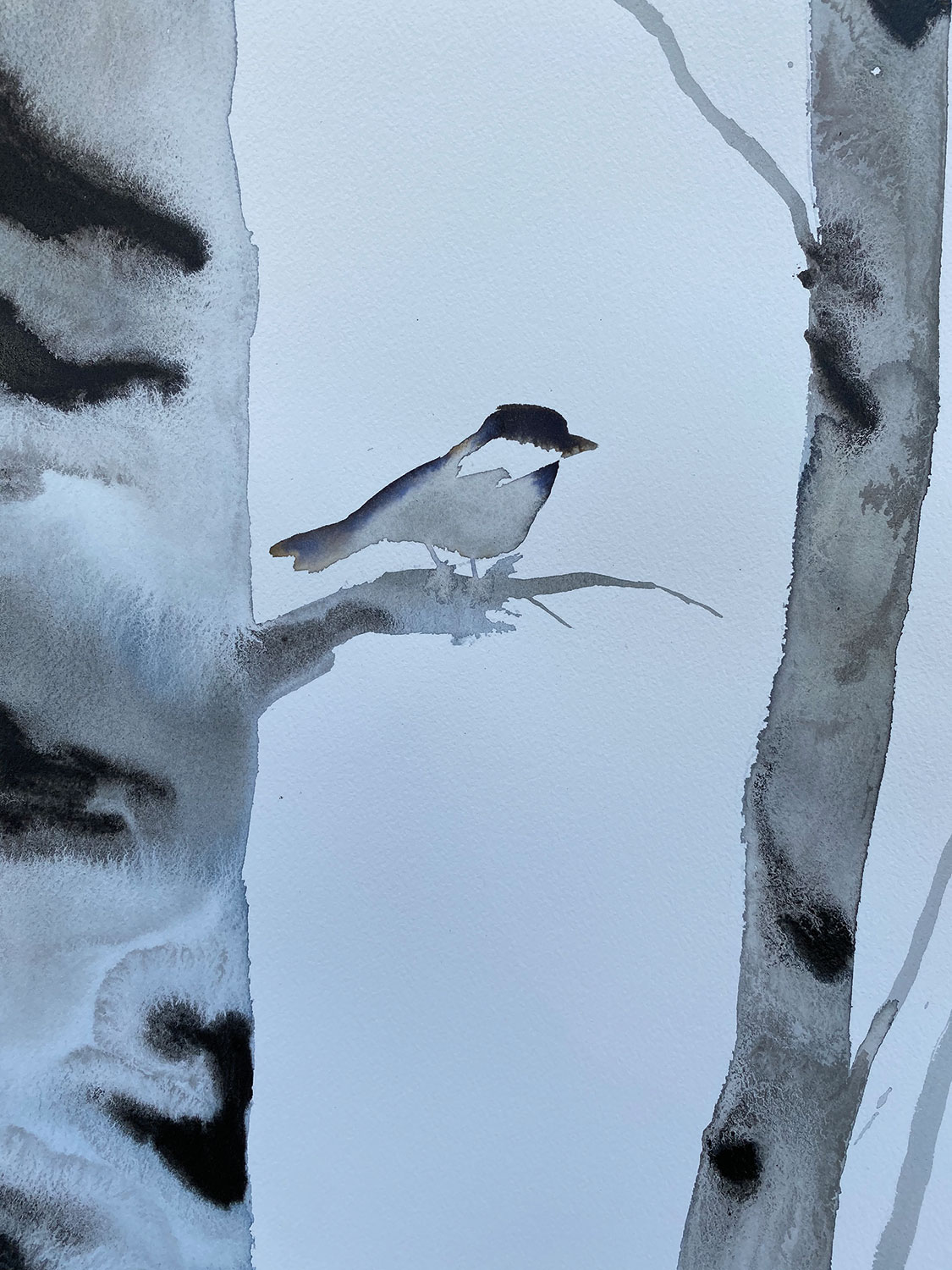

Mountains and reliefs were formed as a result of complex orogenetic phenomena of subsidence that have raised enormous accumulations of marine sediments above sea level. Flora has covered them in various ways and progressively depending on the altitude, on the sun exposure and on the edaphic (soil), climatic and geographical condition of the massif. It is therefore possible to distinguish altitudinal bands, each of which has a characteristic vegetation and therefore a specific plant landscape. My favorite is the one that extends beyond the alpine forest, that intermediate zone that corresponds to the upper limit of the vegetation, where there are mainly isolated subjects of spruce, larch, dwarf willow, mountain pine, stone pine and alder and dwarf shrubs, such as juniper, rhododendron and dog rose, interspersed with large grazing areas.

In summer, the beauty of this habitat is accentuated by the abundant blooms that stand out in its pastures and by the numerous herbaceous plants that are reborn after the winter rest. You can find in abundance masterwort (Peucedanum ostruthium L.), bistort (Polygonum bistorta), French sorrel (Rumex sculatus), lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis idaea), brooklime, dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), monk’s-rhubarb (Rumex alpinus), spotted gentian (Gentiana punctata), potentilla (Potentilla), malva (Malva sylvestris), Lincolnshire spinach (Chenopodium bonushenricus), butterburs (Petasites), coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), plantago (Plantago L.), epilobium (Epilobium), angelica (Angelica), wild carrot (Daucus carota), bladder campion (Silene vulgaris), lady’s mantle (Alchemilla vulgaris) and many other species.

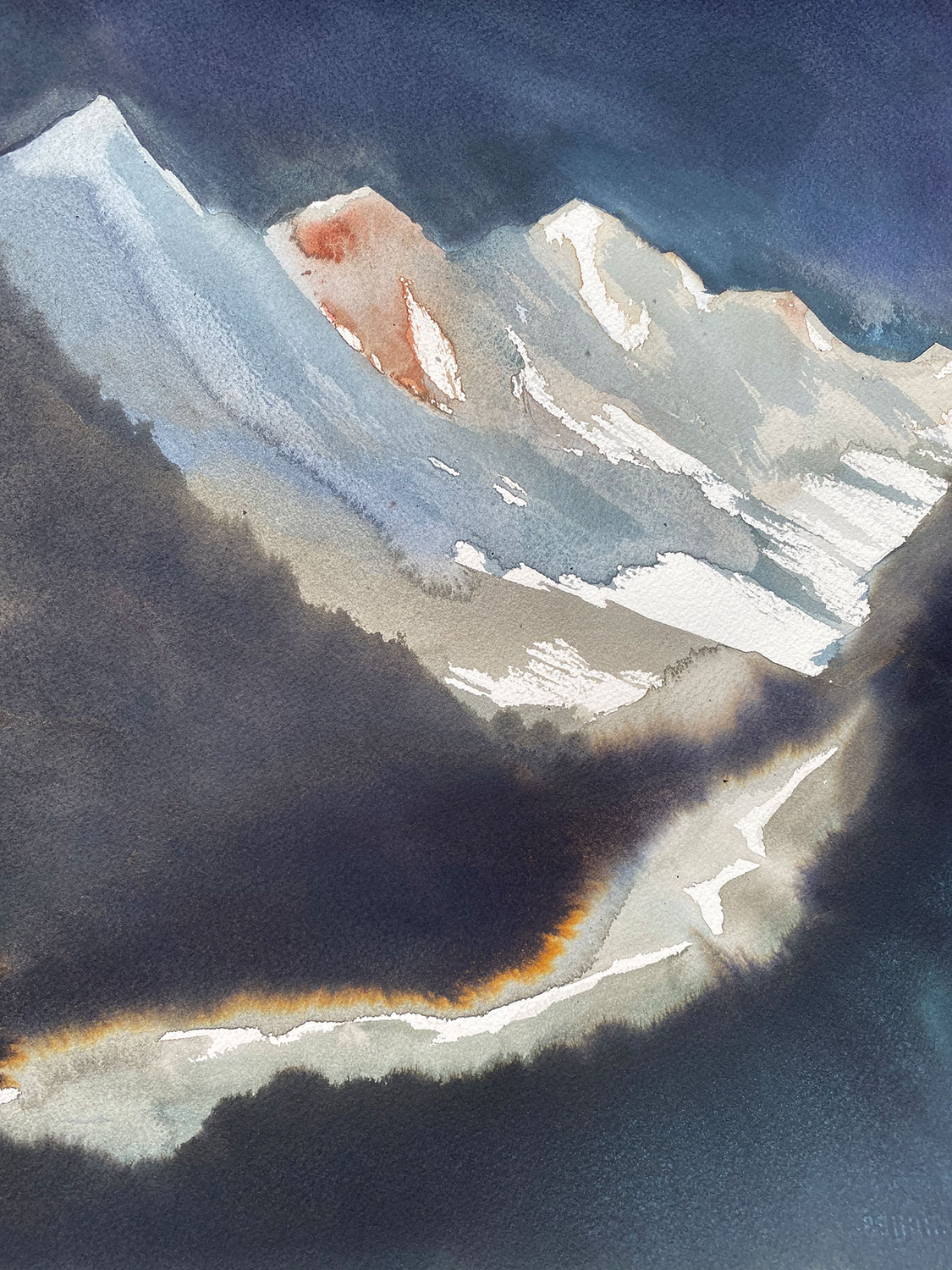

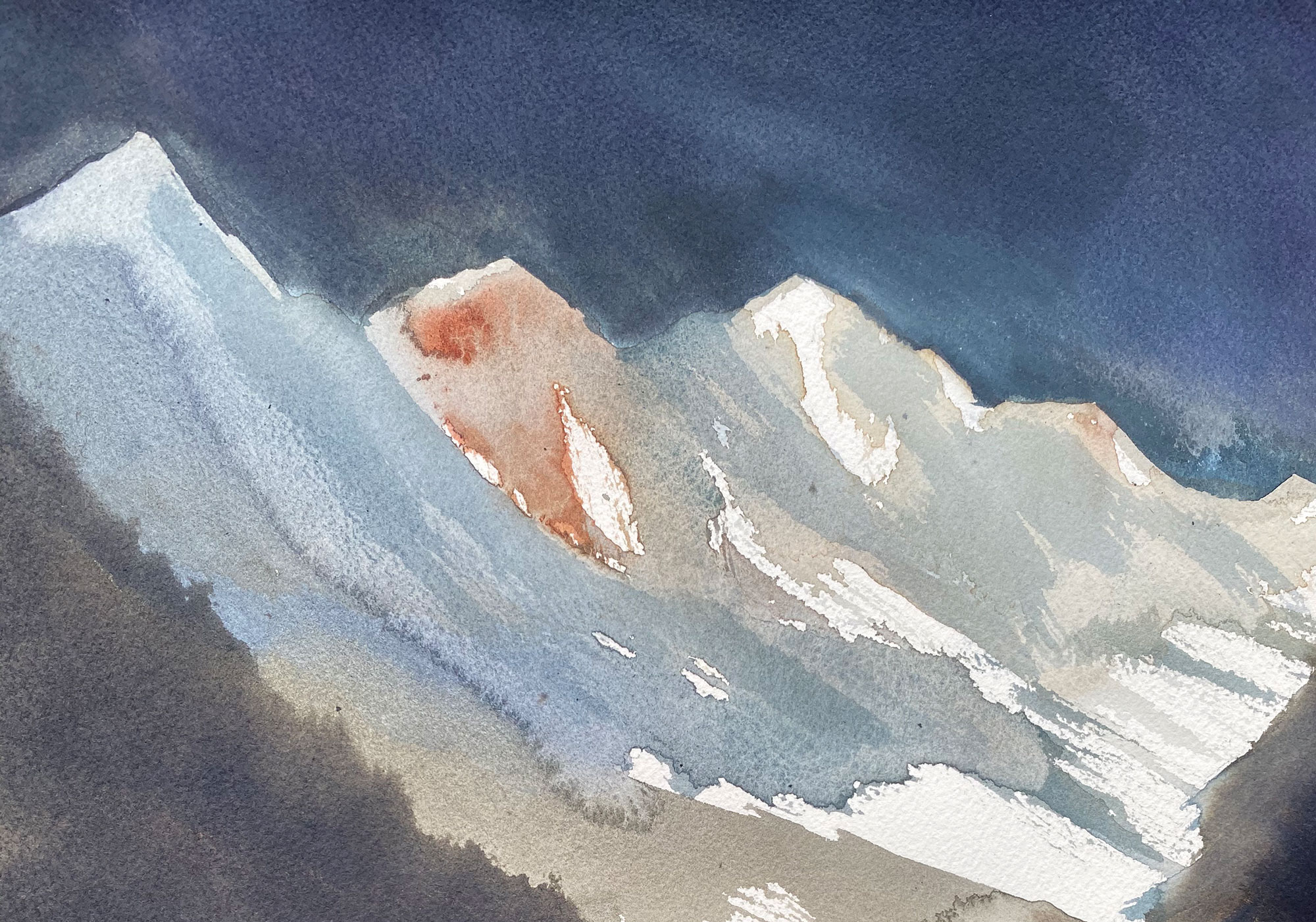

By listing these species and imagining this habitat, the beautiful views of “my mountain”, Valmalenco, immediately come to mind. And here appears in my memories, at the bottom of Chiareggio valley, designed by the strength of Mallero, the plain of Forbesina with the last pioneer houses, and then up, on the left, Val Sissone, a treasure chest of refined minerals and special stones, under the north face of Disgrazia. The Forbesina plain for me is a dream place. Here three valleys converge which, with their own shape, intertwine, an almost perfectly cross. In order are Muretto, which descends from north-west and overlooks Engadine on the other side, Ventina, which arrives steep and threatening from south-east, and the sparkling and less explored Sissone, from south-west. It is towards this side that my attention always moves, and this is where Nicola Magrin lives, my true friend and lifelong travel companion, to whom the wonderful illustrations inspired by our valley accompanying this writing belong, and that are included in his unmissable book “Altri voli con le nuvole” published by Salani.

My gaze is always captivated by that narrow corner that turns right, hiding the valley. As a child I used to go there with my grandfather, looking for stones and minerals, sure, every morning, that this would be the perfect day to find a treasure. The path was hard once I crossed the plain and, each time, it seemed like a new challenge. In the evening I returned home triumphant and weighed down by the grams of my treasures. Nicola, on the other hand, goes there almost every day. He told me that for him it has become a place of thought, where the silence and the suggestions of the landscape allow him to stop and listen. Val Sissone is known all over the world for the presence of spectacular specimens of minerals, even rare ones and with perfect shapes.

It’s easy to find them due to the geological structure of this area in which rocks of very different origin, composition and age have been mixed. Going through the valley, you will find yourself passing through at least three different geological domains and as many consequent changes in the landscape, until you reach a large basin enclosed by the majestic walls of Monte Disgrazia. It is the undisputed lord of the valley, with his giant serac looming over the sight and its name which seems to evoke unfortunate events but whose etymological origin derives from the local dialect term “desglàcia”, that means to defrost.

Maybe that’s because of the large blocks of ice that suddenly fall on the glacier that bears the same name, suspended over the valley, crumbling hundreds of meters below amidst frightening roars. Its shape is engraved in the batholith of Màsino-Bregaglia, a body of intrusive igneous rocks dating back to about 30 million years ago. The incandescent magma came into contact with the encasing rocks, modifying them profoundly: the high heat in fact led their minerals to reorganize themselves again, generating others, while the expelled fluids, rich in rare elements, provided the raw material for new and unique mineralogical species, different for each rock affected by the phenomena of contact metamorphism. Pure fascination.

How strange this writing, where I talked about everything and nothing, without rhyme or reason, without an end and a beginning, but full of sensational images that I feel deep down when I’m up there. Like Nicola’s.